Abstract:

This study examines the impact of digitalization on the well-being of university faculty in Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico, with an emphasis on digital fatigue resulting from the intensive use of virtual platforms. A mixed-methods design was employed, using interviews and surveys with 300 faculty members. Results show that 72% reported high stress levels, 65% experienced physical fatigue (including back and eye strain), and 60% reported an increased workload following the adoption of digital technologies. The study concludes that institutions must implement training programs and provide institutional support to reduce digital fatigue and strengthen the overall well-being of faculty.

Keywords:

workplace well-being; higher education; job stress; fatigue; educational technology

Resumen:

Este estudio analiza el impacto de la digitalización en el bienestar de docentes universitarios en Colombia, Ecuador y México, con énfasis en la fatiga digital por el uso intensivo de plataformas virtuales. Se empleó un enfoque mixto con entrevistas y encuestas a 300 docentes. Los resultados muestran que el 72 % reportó altos niveles de estrés, el 65 % fatiga física (dolores de espalda y ojos) y el 60 % aumento de carga laboral, tras la adopción tecnológica. Se concluye que es necesario implementar programas de formación y apoyo institucional para reducir la fatiga digital y favorecer el bienestar integral del profesorado.

Palabras clave:

bienestar laboral; educación superior; estrés laboral; fatiga; tecnología educacional

1. Introduction

The digitalization of teaching has significantly transformed higher education, particularly in recent years, when the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of virtual platforms. This transition allowed academic continuity but also brought new challenges for university faculty. One of the most concerning effects is digital fatigue, a phenomenon that affects workplace well-being and the emotional health of educators due to the intensive use of digital technologies. It is characterized by physical and psychological exhaustion associated with technological overload, compromising both productivity and faculty well-being.

The impact of digital fatigue is not uniform; it depends on various factors such as technological infrastructure, levels of faculty training, and institutional policies. In Latin America, the adoption of virtual platforms has been uneven, exacerbating the issue, particularly in contexts where educators lack the necessary support to adapt to new technological tools. Limited resources, insufficient continuous training, and work overload have intensified the effects of digital fatigue among university instructors, affecting their motivation, performance, and mental health.

This article aims to analyze the impact of intensive use of virtual platforms on university teaching, focusing specifically on how these technologies affect faculty workplace well-being. Through a systematic review of recent studies, the article identifies key factors contributing to digital fatigue as well as strategies implemented to mitigate its effects. The research also explores differences among institutions with varying levels of technological infrastructure and support to better understand the conditions under which educators experience this phenomenon.

The study employs a mixed-methods approach that combines qualitative and quantitative analyses. It focuses on studies conducted in Latin American countries, particularly Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico, situating the findings within the region’s specific characteristics. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the impact of digitalization on the quality of life of university faculty and offers recommendations to address digital fatigue through integrated strategies involving both professional development and institutional support.

2. Literature review

Digital fatigue among university faculty

Digital fatigue has become a central concern within the educational sector, particularly against the backdrop of the rapid digitalization spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic. This phenomenon denotes the physical and emotional exhaustion experienced by faculty due to the intensive and prolonged reliance on technological platforms for their teaching activities. Recent studies have directly correlated this type of fatigue with a decline in educators’ mental and physical health, often compounded by insufficient institutional preparedness and a noticeable absence of adequate support strategies (Cajas-Bravo et al., 2025; Cherniss, 2010). This consequential impact is further documented by Calzadilla-Pérez (2022), whose work analyzes stress and burnout among educators during the pandemic.

In this context, the study conducted by Herrera-Sánchez et al. (2023) in Ecuador identified technostress as a crucial determinant of digital fatigue among university faculty. Their findings suggest that overexposure to digital tools contributes to debilitating symptoms such as physical exhaustion, eye strain, reduced performance, and an overall decline in personal well-being (Calzadilla-Pérez, 2022). Similar patterns are evident across other Latin American settings, where underlying issues like inadequate infrastructure and limited technological training exacerbate the problem. Consistent with this, Gervacio Jiménez and Castillo Elías (2022) provide detailed documentation of the socio-emotional impacts, coping mechanisms, and specific challenges educators navigated during the pandemic. Similarly, Rodríguez González et al. (2022) analyzed job stress among nursing professionals during COVID-19, a professional context that shares comparable high workload and demanding conditions.

At the institutional level, Goyes-García et al. (2021) explored how the shift to virtual teaching profoundly affected the emotional health of instructors in Colombia. Their qualitative analysis demonstrated that the sudden transition to digital modalities induced significant work overload and a pervasive sense of emotional disconnection. This challenging situation is often intensified when institutional platforms lack sufficient technical support or fail to meet basic ergonomic conditions (Goyes-García et al., 2021). The educational policy landscape analyzed by Jerrim and Sims (2020), alongside Bellei’s (2001) sociological examination of Latin American educational reforms, also provides a vital framework for understanding these structural challenges. Regionally, Dávila Morán and López Gómez (2025) report that digital fatigue risks becoming a chronic issue in Latin America if proactive preventive measures are not implemented, underscoring the urgent need for universities to adopt policies that prioritize the digital well-being of their educators.

In a related vein, Cajas Bravo et al. (2025) emphasize the necessity of institutional policies that tackle digital fatigue through comprehensive, holistic approaches. Their research in Mexico indicates that universities which actively manage digital stress and foster continuous training in technological tools achieve demonstrably better outcomes. Ramírez Díaz et al. (2022) further broaden this perspective by analyzing the biopsychosocial effects on faculty, concluding that the intensive use of technology during lockdown significantly undermined their overall health. As demonstrated across this body of literature, digital fatigue is a multifaceted phenomenon involving both technological and deep-seated psychosocial factors. Methodologically, the reviewed studies consistently integrate both quantitative and qualitative research perspectives (Hernández et al., 2014).

Impact on faculty workplace well-being

The workplace well-being of university instructors is intrinsically tied to the conditions under which they execute their duties, particularly within the context of accelerated digitalization. Molina-Gutiérrez et al. (2025) examine how the enforced adoption of digital technologies has adversely affected faculty mental and physical health. They note that instructors reporting high stress levels also show significant declines in overall well-being, a trend that is especially pronounced in nations with limited technological infrastructure. In this regard, Magro Gutiérrez’s (2021) dissertation, which explores faculty competencies and skills, and Marín Álvarez’s (2022) study on mathematics instructors’ perceptions, offer pertinent perspectives on the challenges inherent in digital education.

Complementing this view, Herrera-Sánchez et al. (2023) demonstrate that technology-induced job stress impacts not only productivity but also teacher motivation, with those in less-resourced institutions proving most vulnerable. This study underscores the need for comprehensive interventions that simultaneously address both technical and emotional aspects. Clearly, universities must implement policies aimed at improving workplace well-being. Hargreaves (2000) emphasizes that teacher well-being is closely linked to effective emotional management, given that adapting to novel tools often generates significant frustration.

The analysis by Dabrowski et al. (2025) reinforces the premise that faculty well-being hinges not merely on working conditions but also on the quality of social support available within institutions. Klassen and Chiu (2010), through a meta-analysis, show that self-efficacy and job satisfaction are strongly connected to teacher well-being, and these crucial factors can be negatively affected by technological overload. Goyes-García et al. (2021) also highlight the critical role of stress-management capabilities. Research conducted during the pandemic further emphasizes that flexibility, robust institutional support, and a sense of control function as key protective factors. Furthermore, studies like Troya-Gutiérrez and Martínez (2022), which analyzes emotional control in patients with acute myocardial infarction, illuminate the relevance of emotional regulation even in high-pressure professions outside of academia.

Strategies to mitigate digital fatigue

To effectively combat digital fatigue among university faculty, a range of strategies have been proposed. Dávila Morán and López Gómez (2025) recommend implementing continuous training programs focused on developing digital competencies. They stress the importance of providing readily available psychological support, an approach strongly reinforced by the systematic review by Silva et al. (2021), which documented high rates of stress and anxiety within the educational sector during the pandemic.

Herrera-Sánchez et al. (2023) emphasize the crucial roles of active breaks and digital disconnection as essential preventive measures. Creating a collaborative work environment is equally essential for reducing digital fatigue. Cooperative learning, as analyzed by Adeyemi (2008), can serve as an effective strategy to mitigate stress by fostering peer support. In this specific context, studies such as Agyapong et al. (2020), which examine psychological support programs delivered via text messaging, demonstrate the feasibility of employing innovative interventions to support mental health.

Resilience and emotional intelligence emerge as crucial personal strategies. Retana-Alvarado et al. (2022) observe that instructors who utilize effective coping strategies are better equipped to mitigate the negative effects of stress. This perspective aligns closely with Masten’s (2001) seminal work on resilience processes and Howard-Jones’s (2014) studies concerning neuroscience in education. Emotional intelligence -first conceptualized by Salovey and Mayer (1990) and subsequently popularized by Goleman (1995)- has proven to be a key factor in preventing burnout. These capabilities, alongside the development of positive psychological capital explored by Luthans et al. (2007), are fundamental for individual well-being. Insights from studies like Aguirre-Arancibia and Marín Álvarez (2024) regarding emotions in physics teaching further reinforce these findings.

Consistent with this, Capone and Petrillo (2020) highlight that mental health, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction are central elements in preventing teacher burnout, thus offering a robust conceptual framework for understanding these phenomena. Workload as a stress factor has been extensively documented by Jerrim and Sims (2020) and Magalong and Torreon (2021), who confirm that poor task management negatively affects teacher well-being and effectiveness, findings that significantly complement the discussions surrounding digital fatigue.

Finally, Rosero (2025) stresses the importance of adopting proactive mental health approaches and highlights the clear relationship between digital fatigue and broader mental health issues. Similarly, Dabrowski (2020) explores teacher well-being during the pandemic. The study by Montoya Grisales and González Palacio (2022) on musculoskeletal disorders, stress, and quality of life among teachers supports this viewpoint. Recent research consistently reveals that musculoskeletal disorders and chronic stress are closely interrelated, suggesting that well-being protocols may be particularly relevant in high-pressure environments.

3. Method

This study employed a mixed-methods design, integrating both qualitative and quantitative techniques to comprehensively analyze the impact of intensive virtual platform use on the workplace well-being of university faculty in Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico. This strategic approach enabled the researchers to effectively capture both the subjective dimension of faculty experiences and statistical patterns that can be generalized to similar educational contexts. The following sections detail the study phases, instrument validation, analytical techniques, and the rationale underpinning the design and sampling strategy.

The qualitative phase utilized semi-structured interviews and focus groups, chosen for their suitability in exploring individual and collective perceptions regarding the digitalization of teaching. Thirty individual interviews (10 per country) were conducted with faculty members from diverse disciplines, age groups, academic trajectories, and varying levels of familiarity with educational technologies.

Participants were selected via purposive sampling using theoretical criteria, prioritizing diversity across academic fields, prior experience with virtual teaching environments, and active employment during both the pandemic and post-pandemic periods. Inclusion criteria required participants to be active university instructors within the past two years, possess experience with virtual teaching, and agree to voluntary participation. Exclusion criteria were defined as educators lacking any contact with digital platforms or those with fewer than six months of teaching experience during the study period.

Interviews probed the subjective experiences of digital fatigue, defined as a cumulative state of emotional, physical, and cognitive exhaustion resulting from the sustained use of digital technologies in teaching. Interviews also explored individual and institutional coping strategies, including time management practices, emotional support mechanisms, and adaptation to new tools.

The interview guide was validated through expert review (n = 5), who assessed the relevance, clarity, and coherence of the items. This feedback allowed for the refinement of questions and ensured alignment with the study objectives.

Interviews were recorded with informed consent, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using thematic coding across three phases: open, axial, and selective coding, with support from Atlas.ti software. Investigator triangulation procedures were implemented to minimize interpretation bias, and researcher influence was consistently monitored through reflective journals and external methodological auditing.

The quantitative phase consisted of a structured survey administered to a sample of 300 university faculty members -100 from each country- selected through nonprobability convenience sampling based on availability and existing experience with virtual education during the study period. This technique was deemed appropriate for accessing participants with specific characteristics across diverse institutional contexts (Hernández et al., 2014).The questionnaire incorporated Likert-type scales, closed-ended questions, and multiple-choice items, facilitating systematic data collection on key variables. These variables were operationalized as follows: digital fatigue was measured through items assessing the frequency and intensity of mental and physical exhaustion associated with digital platform use; workload was analyzed based on the amount of time devoted to academic tasks related to virtual teaching, such as planning, student interaction, and digital administration; and perceived well-being was assessed via items addressing stress symptoms, reported health alterations, and overall emotional balance during remote work.

Validation of the quantitative instrument was executed in two stages: a pilot test with 30 participants to identify any issues regarding wording or ambiguity, and an internal reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha (α = .89), which indicated adequate consistency. Content validity was further ensured through a comprehensive review by experts in educational psychology and technology-enhanced teaching.

Statistical analysis utilized SPSS software and included descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and standard deviations), Pearson correlation coefficients, and bivariate analyses to explore relationships among digital fatigue, workload, and stress levels.

Regarding the integration of methods, the mixed-methods strategy allowed for the combination of qualitative and quantitative results through analytical triangulation, thereby broadening the understanding of digital fatigue from multiple perspectives. This integration involved comparing the rich perceptions collected in the interviews with the statistical patterns derived from the survey to identify convergences, nuances, and potential contradictions. The qualitative analysis provided essential contextual depth, while the quantitative data offered generalizable support for the findings. This comprehensive process ultimately strengthened the validity of the conclusions and informed recommendations grounded in both faculty experiences and robust empirical evidence.

4. Results

The implementation of this study yielded a comprehensive view of how the intensive use of virtual platforms impacts the workplace well-being of university faculty in Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico. The findings reveal both objective and subjective dimensions of the digital fatigue phenomenon, evidenced through responses collected in the survey and narratives from the interviews. The results are presented below, organized into two levels: first, the quantitative analysis, which offers a general overview of observed trends and correlations; and second, the qualitative findings, which provide in-depth insights into the personal experiences of faculty facing the challenges of digital education.

The quantitative component of the study involved administering a survey to 300 university faculty members (100 per country: Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico) to gather information on digital fatigue, workload, stress, and general well-being resulting from the use of virtual platforms in their educational work. The survey included closed-ended questions exploring various aspects of the faculty’s experience with digital teaching, and responses were analyzed using descriptive and correlational statistical techniques to identify the prevalence of the variables and the relationships between them.

Faculty perception regarding the workload associated with the intensive use of digital platforms was specifically investigated. A high percentage of faculty members (82%) reported that their workload increased significantly since the adoption of virtual platforms. Of the 300 respondents, 65% indicated that the time dedicated to class preparation and student interaction had grown, and 72% stated that this increase was directly related to the constant use of digital tools. Table 1 presents the distribution of faculty responses concerning workload changes associated with virtual teaching.

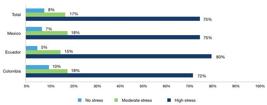

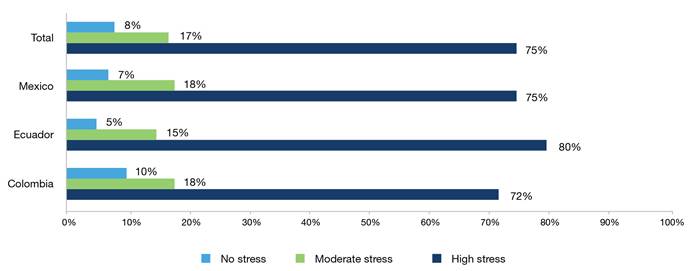

Regarding perceived stress, 75% of faculty reported elevated levels of stress associated with the use of digital platforms. Furthermore, 60% indicated they experienced anxiety levels related to adapting to new technologies and the necessity of being constantly available to students. Concerning general well-being, only 22% felt that their physical and emotional well-being had improved since the transition to digital teaching, as illustrated in Figure 1.

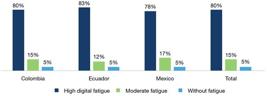

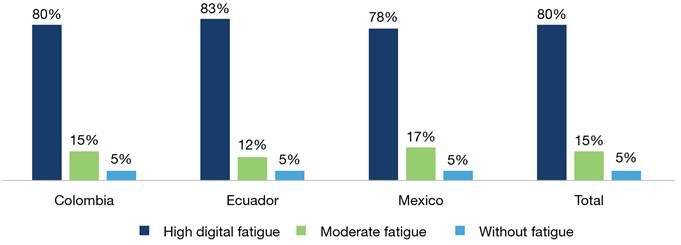

A positive correlation was observed between the perception of digital fatigue and workload. Among the faculty who reported a significant increase in workload, 85% also indicated experiencing high levels of digital fatigue. Additionally, correlational analysis demonstrated a moderate relationship between the frequency of digital platform use and the perception of physical and emotional exhaustion, with a correlation coefficient of .72 (p < .05), as shown in Figure 2.

In the comparison across countries, faculty in Ecuador reported the highest levels of stress (80%) and digital fatigue (83%), followed by those in Mexico (75% and 78%, respectively), and Colombia (72% and 80%, respectively). The results suggest that, while digital fatigue and stress are common issues across all three countries, there are significant variations in the intensity of these experiences, as detailed in Table 2.

The quantitative results demonstrated a notable prevalence of digital fatigue and stress among faculty in all three countries, with variations in the intensity of these factors. The relationship between workload and digital fatigue was highly significant, and the data strongly suggests that the adoption of digital platforms has had a direct impact on the emotional and physical health of university instructors.

The integration of the qualitative and quantitative approaches provided a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon, revealing both the statistical magnitude of the problem and the subjective experiences of the faculty. The interviews provided emotional, physical, and professional nuances that were not fully captured by the survey, while the quantitative data offered a generalizable framework regarding the prevalence of digital fatigue, stress, and workload overload, which is observable in Table 3.

The methodological triangulation confirmed the consistency of the findings. In particular, the overlap between the workload reported in the survey and the exhaustion expressed in the interviews indicates a direct relationship between the intensive use of digital platforms and the deterioration of faculty well-being. Furthermore, the cross-analysis identified that, beyond the increase in work demands, faculty face sustained emotional and physical fatigue that negatively affects their professional performance. Although some have developed coping strategies, the lack of institutional support remains an aggravating factor. This synthesis of results provides a solid foundation for comprehensively understanding the phenomenon and guiding future research and educational policies.

Delving deeper into this dimension, the qualitative findings allowed for a more detailed exploration of the individual and contextual experiences of the faculty. The qualitative component consisted of semi-structured interviews and focus groups with university faculty from the three selected countries: Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico. A total of 30 faculty members were interviewed (10 per country), chosen via purposive sampling to ensure diversity in academic disciplines and experience with digital platform use. The interviews focused on educators’ perceptions of the emotional and physical impact of intensive use of educational technologies. The data obtained were analyzed using a thematic approach, which identified patterns related to stress, anxiety, exhaustion, and the coping strategies employed by faculty, such as emotional self-regulation and resilience.

Regarding perceptions of the emotional impact, faculty reported a significant increase in stress and anxiety levels due to the intensive use of digital platforms. The transition to virtual teaching forced by the pandemic required a reconfiguration of work dynamics, which increased the workload and reduced direct interactions with students, subsequently affecting educators’ motivation. Some faculty noted that, despite having received training in technological tools, the emotional impact of virtual teaching remained overwhelming, particularly the feeling that work demands exceeded their capacities. Perceptions of stress were exacerbated by the difficulty of disconnecting from work, which had negative effects on their general well-being. Faculty responses reflected a widespread perception of emotional exhaustion associated with the continuous use of educational platforms:

“The intensive use of virtual platforms has increased stress in my work. Before the pandemic, I had a more balanced control over my classes, but now the workload is much heavier. Interaction with students has become more superficial, and that affects my motivation.” (Professor from Colombia, May 20, 2023)

“The most complicated part has been adapting to new technologies. While I have received training, it’s not enough when the emotional impact is so large. I find it hard to disconnect from work, and that affects my physical well-being. Sometimes I feel like the work never ends, which generates constant stress that affects me even outside work hours.” (Faculty member from Ecuador, June 27, 2023)

In relation to the physical impact, faculty indicated that digital fatigue manifested primarily through musculoskeletal ailments, such as back and neck discomfort resulting from prolonged screen time. The work overload, coupled with the increased time in front of the computer, led not only to mental exhaustion but also to significant physical wear and tear. Faculty highlighted that, while technology offered certain advantages for teaching, the negative effects on their physical health were evident, especially due to the lack of a proper work-life balance. Many of the interviewees commented that the feeling of being “always connected” contributed to general exhaustion, exacerbated by a lack of adequate breaks and a space for disconnection outside work hours. This sense of being permanently in “work mode” amplified the feeling of fatigue, producing both physical and emotional consequences:

“It’s difficult to find a balance between online teaching and my personal life. I feel like I’m always connected, answering emails, preparing materials, and adjusting the platforms. Sometimes I feel overwhelmed and can’t disconnect. Physical ailments like back pain are also a constant problem due to screen time.” (Faculty member from Ecuador, May 25, 2023)

“Digital fatigue is real, and I feel that even though I’ve learned to use technological tools, I lack institutional support regarding emotional well-being. It’s a burden that isn’t sufficiently recognized.” (Faculty member from Mexico, July 5, 2023)

Some faculty mentioned that, to manage the stress and fatigue derived from the intensive use of digital platforms, they implemented various coping strategies, such as emotional self-regulation and resilience. However, these defense mechanisms were not always sufficient to counteract the negative effects of digitalized work. Others noted that, while they attempted to implement breaks and manage time better, the constant screen exposure and lack of direct student interaction hindered the effectiveness of these strategies. The majority agreed that the lack of continuous training and institutional support, both in training and emotional well-being, increased the workload. Implementing activities that allowed for disconnection, such as taking active breaks or promoting fewer formal interactions with students, proved to be a way to mitigate the negative effects of virtual teaching. Nonetheless, most faculty concurred that these strategies were often inadequate for effectively coping with the emotional fatigue resulting from digital work:

“Emotional exhaustion is one of the most visible effects. Online teaching, while convenient, doesn’t replace face-to-face interaction with students. It’s hard to keep their attention or enthusiasm, and that affects me personally. The lack of continuous training also makes me feel lost when facing new platforms and tools.” (Faculty member from Colombia, April 10, 2022)

“Stress has increased significantly, especially because now I’m more concerned with the platforms than with my students. Sometimes I feel that, no matter how hard I try, I’m not achieving the expected results. I’ve implemented resilience strategies, like taking short breaks, but they are not always sufficient to prevent emotional fatigue.” (Faculty member from Mexico, July 5, 2023)

5. Discussion and conclusions

The execution of this study provided a comprehensive understanding of how the intensive use of virtual platforms impacted the workplace well-being of university faculty across Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico. The findings uncovered both objective and subjective dimensions of the digital fatigue phenomenon, evidenced by the survey responses and the narratives gathered from the interviews. The quantitative analysis showed that 82% of faculty perceived a significant increase in workload due to the adoption of digital platforms, while 75% reported elevated levels of stress associated with their use. These results suggest that the virtual modality increased not only the volume of work but also the emotional pressure, generating a negative impact on the general well-being of the teaching staff, a finding that aligns with prior research (Molina-Gutiérrez et al., 2025).

The link between workload and digital fatigue was clearly established, as 85% of those reporting a greater workload also noted high levels of fatigue, and the correlation between frequency of use and physical and emotional exhaustion reached a coefficient of .72 (p < .05). These data confirm that the rise in digital work demands translates directly into physical and emotional fatigue (Goyes-García et al., 2021). Of particular note is the greater intensity of these phenomena in Ecuador, with 83% reporting digital fatigue. This might be attributable to differences in institutional conditions, technological infrastructure, and support policies, factors that Herrera-Sánchez et al. (2023) and Reyes-Ruíz et al. (2023) have pointed to as crucial for understanding technological stress in specific contexts.

The qualitative component supplemented this view by providing testimonials that expressed the emotional and physical toll experienced by faculty. Many pointed out that, despite receiving technological training, the constant demand to be available and connected generated anxiety and exhaustion. These experiences confirm that technical training alone is insufficient to mitigate stress and concur with Retana-Alvarado et al. (2022), who highlight the importance of comprehensive support that includes emotional well-being and effective coping strategies. Emotional intelligence and resilience, as suggested by Goleman (1995) and Cherniss (2010), are key factors in preventing faculty burnout, reinforcing the need to integrate these components into any wellness program.

Regarding physical aspects, faculty reported musculoskeletal ailments as a direct consequence of prolonged screen time and work overload, leading to back problems and muscle tension. Physical fatigue, linked to emotional strain, impacts not only health but also professional performance, a finding that expands upon documentation by Ramírez Díaz et al. (2022), Montoya Grisales and González Palacio (2022), and Calzadilla Pérez (2022) on the relevance of ergonomic conditions and active breaks in reducing the negative impact of digitalized work. Indeed, the lack of well-being protocols in high-pressure contexts, such as those studied by Soria-Pérez et al. (2022), exacerbates these health issues.

The lack of institutional support to address these challenges was a recurring theme in the testimonials, limiting the effectiveness of individual coping strategies implemented by faculty. The absence of clear policies and resources for faculty well-being contributes to the perpetuation of digital fatigue, reaffirming the need for institutional interventions that promote disconnection and provide continuous support (Dávila Morán & López Gómez, 2025; Rosero, 2025). Arnett’s (2016) research, which critiques the predominantly Western focus in psychology, suggests that these policies must be culturally sensitive and adapted to the realities of each country.

In summary, the study evidenced that the intensive use of virtual platforms significantly increased the workload, stress, and digital fatigue of university faculty in the three countries analyzed. The combination of quantitative and qualitative methods allowed for an understanding of the magnitude and complexity of the phenomenon, demonstrating how the virtual environment affects multiple dimensions of faculty well-being. Nevertheless, the research has important limitations, such as the restricted sample size and the cross-sectional design, which limit the generalizability and temporal analysis of the problem (Arnett, 2016; Hernández et al., 2014). Future research should consider larger, longitudinal samples to explore the development of digital fatigue and evaluate the efficacy of institutional interventions aimed at improving faculty well-being, such as support and stress management strategies.

References

-

Adeyemi, B. A. (2008). Effects of cooperative learning and problem-solving strategies on junior secondary school students’ achievement in social studies. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 6(3), 691-708. https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v6i16.1294

» https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.v6i16.1294 -

Aguirre-Arancibia, P., & Marín-Álvarez, F. (2024). ¿Hay lugar para lo emocional en la enseñanza de la física universitaria? Un acercamiento desde el relato del docente. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 23(53), 123-138. https://doi.org/10.21703/rexe.v23i53.2414

» https://doi.org/10.21703/rexe.v23i53.2414 -

Agyapong, V. I. O., Hrabok, M., Vuong, W., Gusnowski, A., Shalaby, R., Mrklas, K., Li, D., Urichuk, L., Snaterse, M., Surood, S., Cao, B., Li, X. M., Greiner, R., & Greenshaw, A. J. (2020). Closing the psychological treatment gap during the COVID-19 pandemic with a supportive text messaging program: protocol for implementation and evaluation. JMIR Research Protocols, 9(6), e19292. https://doi.org/10.2196/19292

» https://doi.org/10.2196/19292 -

Arnett, J. J. (2016). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. En A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research (pp. 115-132). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14805-008

» https://doi.org/10.1037/14805-008 -

Bellei, C. (2001). El talón de Aquiles de la Reforma. Análisis sociológico de la política de los 90 hacia los docentes en Chile. En S. Martinic & M. Pardo (Eds.), Economía política de las reformas educativas en América Latina (pp. 129-146). PREAL-CIDE. https://r.issu.edu.do/5Y

» https://r.issu.edu.do/5Y -

Cajas Bravo, V. T., Lopez Gomez, H. E., Sanchez Soto, J. M., & Silva Infantes, M. (2025). Fatiga digital y su efecto en el desempeño docente universitario. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 30(Especial 13), 521-537. https://doi.org/10.52080/rvgluz.30.especial13.34

» https://doi.org/10.52080/rvgluz.30.especial13.34 -

Calzadilla-Pérez, O. (2022). Bases neuroeducativas del estrés y su relación con el rendimiento académico. Pedagogía, 22(79), 1729-8091. https://r.issu.edu.do/hA

» https://r.issu.edu.do/hA -

Capone, V., & Petrillo, G. (2020). Mental health in teachers: relationships with job satisfaction, efficacy beliefs, burnout and depression. Current Psychology, 39, 1757-1766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9878-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9878-7 -

Cherniss, C. (2010). Emotional intelligence and organizational effectiveness. En C. Cherniss & D. Goleman (Eds.), The emotionally intelligent workplace (pp. 3-13). Jossey-Bass. https://r.issu.edu.do/d8T

» https://r.issu.edu.do/d8T -

Dabrowski, A. (2020). Teacher wellbeing during a pandemic: surviving or thriving?. Social Education Research, 2(1), 35-40. https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021588

» https://doi.org/10.37256/ser.212021588 -

Dabrowski, A., Hsien, M., Van Der Zant, T., & Ahmed, S. K. (2025). «We are left to fend for ourselves»: understanding why teachers struggle to support students’ mental health. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1505077. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1505077

» https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1505077 -

Dávila Morán, R. C., & López Gómez, H. E. (2025). Fatiga digital en docentes universitarios post-pandemia: Asociación con rendimiento y bienestar laboral. Universidad y Sociedad, 17(1), e4927. https://r.issu.edu.do/gE

» https://r.issu.edu.do/gE -

Gervacio Jiménez, H., & Castillo Elías, B. (2022). Impactos socioemocionales, estrategias y retos docentes en el nivel medio superior durante el confinamiento por COVID-19. RIDE. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 12(24), e010. https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v12i24.1133

» https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v12i24.1133 -

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ Bloomsbury. https://r.issu.edu.do/fD

» https://r.issu.edu.do/fD -

Goyes-García, J. F., Romero-Fernández, A. J., Alfonso-González, I., & Latorre-Tapia, L. F. (2021). Desgaste emocional de docentes universitarios en entornos virtuales de formación en período de contingencia sanitaria. Conrado, 17(81), 379-386. https://r.issu.edu.do/exC

» https://r.issu.edu.do/exC -

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: Teachers’ perceptions of their interactions with students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(2000), 811-826. https://r.issu.edu.do/EV3

» https://r.issu.edu.do/EV3 -

Hernández, R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (2014). Metodología de la investigación (6.ª ed.). McGraw-Hill. https://r.issu.edu.do/ZMZ

» https://r.issu.edu.do/ZMZ -

Herrera-Sánchez, M. J., Casanova-Villalba, C. I., Bravo Bravo, I. F., & Barba Mosquera, A. E. (2023). Estudio comparativo de las desigualdades en el tecnoestrés entre instituciones de educación superior en América Latina y Europa. Código Científico Revista de Investigación, 4(2), 1288-1303. https://doi.org/10.55813/gaea/ccri/v4/n2/287

» https://doi.org/10.55813/gaea/ccri/v4/n2/287 -

Howard-Jones, P. A. (2014). Neuroscience and education: Myths and messages. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15, 817-824. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3817

» https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3817 -

Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2020). Teacher workload and well-being: New international evidence from the OECD TALIS study. Teaching and Teacher Education https://r.issu.edu.do/8Df

» https://r.issu.edu.do/8Df -

Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 535-548. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019237

» https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019237 -

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541-572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x -

Magalong, A. A., & Torreon, L. C. (2021). Teaching workload management: its impact on teachers’ well-being and effectiveness. American Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 3(2), 31-36. https://r.issu.edu.do/l2ca

» https://r.issu.edu.do/l2ca -

Magro Gutiérrez, M. (2021). Competencias y habilidades para el desarrollo de la práctica docente en escuelas infantiles rurales multigrado. Estudio comparado entre México y España [Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Camilo José Cela]. https://r.issu.edu.do/l?l=12685SnS

» https://r.issu.edu.do/l?l=12685SnS -

Marín Álvarez, F. (2022). Percepciones en docentes de matemáticas universitarias sobre el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en tiempos de pandemia. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 21(47), 169-184. https://doi.org/10.21703/0718-5162202202102147009

» https://doi.org/10.21703/0718-5162202202102147009 -

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227-238. https://r.issu.edu.do/ez5K

» https://r.issu.edu.do/ez5K -

Molina-Gutiérrez, T. de J., Arias-Collaguazo, W. M., Meza-Molina, D. A., & Burbano-García, L. H. (2025). Agotamiento laboral en docentes universitarios: una perspectiva desde la autoexigencia y el perfeccionismo. Revista Mexicana de Investigación e Intervención Educativa, 4(S1), 6-17. https://doi.org/10.62697/rmiie.v4iS1.142

» https://doi.org/10.62697/rmiie.v4iS1.142 -

Montoya Grisales, N. E., & González Palacio, E. V. (2022). Musculoskeletal disorders, stress, and life quality in professors of Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje. Revista de Investigación e Innovación en Ciencias de la Salud, 4(2), 5-19. https://doi.org/10.46634/riics.138

» https://doi.org/10.46634/riics.138 -

Ramírez Díaz, I. M., Herrera Mijangos, S. N., & Luna Reyes, D. (2022). Práctica profesional y repercusiones biopsicosociales de docentes de educación media superior por el confinamiento en Hidalgo, México. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo, 12(24), e348. https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v12i24.1189

» https://doi.org/10.23913/ride.v12i24.1189 -

Retana-Alvarado, D. A., González-Ríos, J., & Pérez-Villalobos, D. (2022). Afrontamiento emocional implementado por las personas docentes en Costa Rica para el manejo del estrés. InterSedes, 23(47), 161-183. https://doi.org/10.15517/isucr.v23i47.48375

» https://doi.org/10.15517/isucr.v23i47.48375 -

Reyes-Ruíz, F., López-García, Y., Ortega-Pérez, M. I., Sevilla-González, M. de la L., González-Díaz, G., & Sibaja-Terán, B. (2023). Fatiga y teletrabajo en docentes de Latinoamérica. Una necesidad urgente de estudio.Ergonomía, Investigación y Desarrollo

,5(2), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.29393/EID5-15FTFR60015

» https://doi.org/10.29393/EID5-15FTFR60015 -

Rodríguez González, Z., Ferrer Castro, J. E., & De la Torre Vega, G. (2022). Estrés laboral en profesionales de enfermería de una unidad quirúrgica en tiempos de la COVID-19. MEDISAN, 26(5), e4306. https://r.issu.edu.do/4J

» https://r.issu.edu.do/4J -

Rosero, S. (2025). Más allá de las notas: Salud mental y suicidio en el ámbito universitario. Revista Realidad Educativa, 5(1), 110-142. https://doi.org/10.38123/rre.v5i1.474

» https://doi.org/10.38123/rre.v5i1.474 -

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

» https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG -

Silva, D. F. O., Cobucci, R. N., Lima, S. C. V. C., & de Andrade, F. B. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review. Medicine, 100(44), e27684. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000027684

» https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000027684 -

Soria-Pérez, R., Agüero-Martínez, M. O., de Armas-Mestre, J., Díaz-Camellón, D. J., & Benítez-Ruiz, A. (2022). Protocolo de recuperación acelerada en adultos mayores con fracturas de miembros inferiores. Cárdenas, 2015-2019. Revista Médica Electrónica, 44(3), 495-507. https://r.issu.edu.do/wr

» https://r.issu.edu.do/wr -

Troya-Gutiérrez, A. G., & Martínez, C. A. (2022). Práctica de Enfermería para control emocional en personas con antecedentes de infarto agudo de miocardio. Medicentro Electrónica, 26(3), 771-780. https://r.issu.edu.do/tKE

» https://r.issu.edu.do/tKE

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

30 Nov 2025 -

Date of issue

2025

History

-

Received

04 Feb 2025 -

Reviewed

14 July 2025 -

Accepted

03 Sept 2025 -

Published

30 Nov 2025

Digital Fatigue among University Faculty: Impact of Intensive Use of Virtual Platforms on Teaching and Workplace Well-Being

Digital Fatigue among University Faculty: Impact of Intensive Use of Virtual Platforms on Teaching and Workplace Well-Being